The Cold War began almost the day after the end of World War II, with recent allies on opposite sides of the barricade. It was then that another global conflict would soon break out. Since then there was “peace that is not peace.”

“Cold War” became a term for an international conflict that could not be resolved by direct military confrontation. As it unfolded, it was a state of high tension and hostile rivalry between the USSR and its satellite states, and non-communist states under US leadership. In trivialization, the Cold War was a struggle between two opposing systems for leadership or world domination, in which the USSR and the US played the main roles. It lasted from the end of World War II to 1991.

The term “cold war” was first used by British writer George Orwell in his essay “You and the Atom Bomb” in the Tribune on October 19, 1945. In turn, two speeches are considered to be the appropriate inauguration of the conflict. The first was delivered by Stalin in Moscow on February 9, 1946 – the Soviet leader then announced the inevitable necessity of a war with Western imperialists. Soon, on March 5 of the same year, Winston Churchill delivered a speech in the American Fulton – it was then that the characteristic words were uttered: “From Szczecin on the Baltic to Trieste on the Adriatic, the iron curtain has fallen on the continent.”

After the end of World War II, relations between the recent coalition partners continued to deteriorate. The confrontations sparked by Stalin multiplied, and then Iran, Turkey and finally Greece became the next hot spots. Therefore, the USA announced the implementation of the principles of stopping the expansion of communism by all available means, known more broadly as the “Truman Doctrine”. These intentions were signaled by the American president himself during his speech to Congress on March 12, 1947.

From that moment on, until the end of the Cold War, this concept was one of the cornerstones of American politics. This doctrine was supplemented by the beneficial economic aid plan, commonly known as the “Marshall Plan”. Stalin was obviously against this project, which meant excluding Poland from it, and most importantly – the final division of the European continent into two opposing blocs.

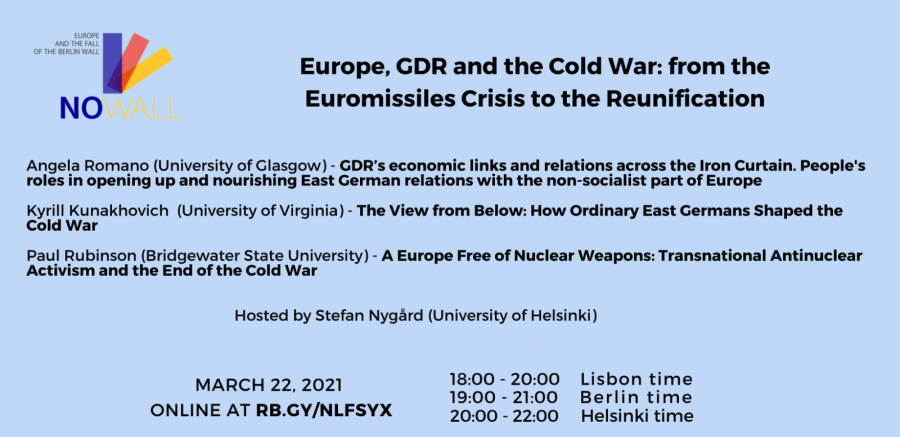

22 March | 18:00 – 20:00 Lisbon time | 19:00 – 21:00 Berlin and Amsterdam time | 20:00 – 22:00 Helsinki time |

Join for free at https://rb.gy/nlfsyx

PROGRAMME

Angela Romano (University of Glasgow) – “GDR’s economic links and relations across the Iron Curtain. People’s roles in opening up and nourishing East German relations with the non-socialist part of Europe”

Angela is an international historian of the 20th Century. Her research spans the Cold War, the variety of regional integration and cooperation processes, regional organisations, international and transnational political and economic relations. She has published extensively on these subjects. She has been invited to present her research in numerous conferences in Europe, Russia, the United States and Japan, and to give keynote speeches and public lectures. In January 2020 she was visiting Associate Professor at the University of Tokyo. Before joining the University of Glasgow, she was Senior Research Fellow at the European University Institute (EUI), where she co-ran the ERC-funded project PanEur1970s (2015-2020); Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow at LSE (2011-2013); and Jean Monnet Fellow at the EUI (2009-10).

Kyrill Kunakhovich (University of Virginia) – “The View from Below: How Ordinary East Germans Shaped the Cold War”

Kyrill is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Virginia, where he teaches courses on communism, fascism, nationalism, and the Cold War. A historian of modern Europe, his particular focus is on central and eastern Europe in the twentieth century. Together with Piotr Kosicki, he is the editor of The Long 1989: Decades of Global Revolution (Central European University Press, 2018). His current book manuscript, tentatively titled Communism’s Public Sphere: Culture as Politics in Cold War Poland and East Germany, is forthcoming from Cornell University Press. Focusing on two cities, Kraków in Poland and Leipzig in the GDR, it examines art’s role in communist politics as well as communism’s impact on the arts.

Paul Rubinson (Bridgewater State University) – “A Europe Free of Nuclear Weapons: Transnational Antinuclear Activism and the End of the Cold War”

Paul is Associate Professor of History at Bridgewater State University. He was born in Baltimore, MD, and graduated with a BA from Vanderbilt University. He served as a Smith-Richardson predoctoral fellow at Yale University International Security Studies in 2007 and received his PhD in history from the University of Texas at Austin in 2008. His current research interests focus on the relationship between scientists and the development of human rights from the 1790s to the 1970s. He is the author of Redefining Science: Scientists, the National Security State, and Nuclear Weapons in Cold War America, published in 2016 by the University of Massachusetts Press, as well as Rethinking the Antinuclear Movement, published in 2017 by Routledge. His articles have appeared in Diplomatic History and Cold War History as well as edited collections on the Cold War, science, and human rights from Routledge, Manchester University Press, and Oxford University Press.

Hosted by Stefan Nygård (University of Helsinki)

Stefan Nygård (University of Helsinki) is a senior researcher of 19th and 20th century European intellectual and political history. His recent publications include Decentering European Intellectual Space (with Marja Jalava and Johan Strang, Brill 2018) and The Politics of Debt and Europe’s relations with the ‘South’ (Edinburgh University Press 2020).